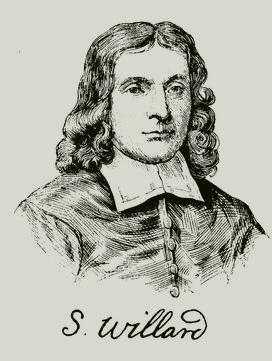

Major Simon Willard: A letter by him

An early American settler from Horsmonden

An early American settler from Horsmonden

A letter written by Major Simon Willard to his children of all generations. Simon Willard, born 1606 in Horsmonden, died 1676.

To my children, – for so I call you, though belonging to different generations, – listen to my words of instruction, warning, and advice. It is my privilege and my duty to hold converse with you, as I have been constituted by our heavenly Father, the founder of a numerous race on these Western shores. Born before the settlement of Jamestown and Plymouth, and of an age to remember the voyage of the ‘Mayflower,’ – the news whereof was brought even to my retired village of Horsmonden, – I was permitted to live through an important epoch, when great principles were in discussion, the settlement of which would affect future generations in the establishment of justice and right, or the perpetuation of wrong under the forms of law.

The death of my mother, of blessed memory, when I was too young to know the extent of my loss, and that of a father in my early youth, not, indeed, before remembered words of counsel and affection, but when I needed his protection and guidance, left me exposed to the temptations which invade the humble village as well as the larger resorts of men. But, though assailed, through God’s mercy I was saved from falling; and trusting in Him whom I had been in youth taught reverence, I was brought safely through.

My early training was in the church of England; and in the ancient parish church I received in my infancy, the waters of baptism by the hands of the rector, Rev. Edward Alchine, from whose instructions and catechetical teachings, when I came of age to understand them, I trust that I received spiritual benefit. But my religious preferences were in another direction, and I yielded to their persuasions. I well remember, even with the dawn of reason and reflection, the great controversy, which was then beginning to range with unwonted heat, even to the dividing of families.

I had none to aid me in shaping my future course; and though I was prospered in business and very happy with the wife of my choice, and might have borne my part in my native village, the feeling increased, that this was not my proper sphere. Neighbors and friends, the men of Kent, in various quarters, were preparing to remove to the New World, where success had attended the Plymouth settlers, and the larger and more imposing colony composed of those who lined the shores of this beautiful bay. I was in sympathy with these Christians, while still loving the church from which I had separated, and the ‘tender milk’ drawn from her breasts.

I saw the day approaching when sharp trials would begin, and I should be excluded from the few religious privileges which remained for those who already were stigmatized as schismatic. I determined to join those who were seeking a home in the wilderness, where we might worship God in a way which we thought was of his appointment. But how was this to be accomplished with a young family? Measures of detention, which had now well-nigh reached their culminating point, were daily becoming more stringent, requiring certificates of uniformity, and oaths of allegiance and supremacy, of all who purposed embarking for the New World. Vessels were carefully watched; and none could leave the realm, and take passage for New England, without special permission, and having submitted to various orders exacted by authority. I closed up my business in Horsmonden, made my preparations diligently and silently in connection with a married sister and her husband, and bidding an affectionate adieu to those of the family left behind, reached the coast in safety, where we found a boat in readiness to take us to the vessel which was to bear us to our coveted retreat.

I cannot describe to you my sensations on forsaking my native land. Scarce ever beyond the bounds of my little village, I was leaving home, with all its fond ancestral associations, never to return. My emotions, on taking the last view of dear Old England, were such as almost to over power me. All of love, all of memory, returned; and I felt for the moment a doubt, whether I was in the way of duty in my removal. But it was only for a moment. When the last speck of Kentish shore disappeared below the horizon, I girded myself to the undertaking; cast no more lingering looks behind, but looked forward over the wide waste of waters towards my detained abode; addressed myself to all that belonged to its duties and obligations; and never at any one moment afterwards, until the day that God called me hence from earthly scenes, did I regret the resolution I had taken. We were favored in our passage, and our little fleet reached these shores in the beautiful noontide of May, when all nature was bursting into life, as if to give us a glad and smiling welcome to the new home of our pilgrimage.

I look around me; but all is changed that is under the power or control of man. In the populous towns and cities which have sprung up, I cannot recognize the little hamlets, once my familiar acquaintance. Even my ancient dwelling places – peaceful and humble abodes in Cambridge, Concord, Lancaster, and Groton – can no longer be traced or divined, except by those marks which God himself has established in the flowing waters of the Charles, the Assabet, and the Nashaway. Strange sights and sounds salute my senses; mysterious agencies of motion on land and water are all around me; and I almost feel as if man was in communion with forbidden spirits.

Descendants, – Here I planted my stakes; here I made my home, nor wished to return to the scenes of my youth. My venture here in new and untried existence, and I loved it. God favored me with health, friends, and beloved children; while, by his will and the love of the brethren, I trust I was helpful to the Commonwealth, at least in some humble measure, in military, legislative, and judicial service, through a long period, until my death. For all that I was enabled to do I was truly grateful, while conscious of my shortcomings, and lamenting that my success did not equal my intentions.

It was my earnest wish to train up my children to walk in paths of virtue and usefulness, and to educate them in human learning according to their capacities, that they might serve their generation with fidelity. Herein I was aided and blessed in the schools, open to all, which our honored magistrates and deputies caused to be established, that ‘learning might not be buried in the grave of our fathers, in church and commonwealth; ‘and by the teachings and instructions of worthy Mr. Bulkeley and Mr. Rowlandson. By their regular attendance on public worship, by observing the ordinances, by worship in the family, my sons and daughters were in the sure way of preparation for good service in life and becoming examples to their own children.

And now, if, in the day of small things, when we were few in number and weak in power, surrounded by the savage, with none under God to help us save our own right arm, I was of any service to church or commonwealth, I desire to first of all thank God, and give him praise. I will not offer myself as an example for imitation, or commend myself for having done aught, but only say that I have endeavored.

Consider what God has done for you. The wilderness and the solitary place have been made glad for you; and the desert rejoices, and blossoms as the rose, as in the days of Isaiah for the chosen people. Indeed, the little one has become a thousand; and the small beginnings, which I witnessed, have widened out to a powerful commonwealth, filled with comforts, privileges, and blessings, countless in number and leaving little to be imagined or desired. Think not that your own right hand has wrought out this your happy condition; but give thanks to Him to whom they belong, and believe that never was a people more highly favored.

You would honor my memory, and are very free in expressing veneration: but if you would honor me aright, if you feel the veneration you express, show it by your deeds; by reverence of that which is higher and holier; by doing all your duty actively and earnestly in your generation; by adhering to the old paths of justice, faithfulness, and holy trust; by sincerity in belief, abandoning all Antinomian heresies as you would the other extreme of dead formalism; by being bold for the right, modestly and firmly maintaining your opinions, whether called to public station or in the more private walks; following no man and no cause because of popularity, shunning no man and no cause you believe to be right because of unpopularity or reproach; but avoiding the parasite and self seeker, and standing bravely by your own convictions. Thus did my son, even Samuel, in the time of his pilgrimage, when he set himself in opposition to the greatest delusion that ever visited this land, subjecting himself to great trial in the coldness of friends, and the harsh judgment of an entire community; but, unmoved in his purpose, sustained by his conscientious view of the right, calmly awaited that revolution in sentiment which at once was the earnest and reward of his long and patient suffering.

“Farewell!”

Simon Willard

From the Willard Memoir; Life and Times of Major Simon Willard, 1858, by Joseph Willard.

*Simon is making reference to his son, Rev. Samuel Willard, who studied witchcraft for twenty-years prior to the Salem Witch trials and took a stance against the Rev. Cotton Mather, an advocate in the matter of the trials.

Simon Willard, with Peter Bulkeley, bought Concord (Mass.) from the native Indians.

For twenty-two years Major Willard held the highest offices in the gift of the people. He was one of the Governor’s council, a member of the Supreme Judicial Court, and deputy to the General Court for fifteen years.