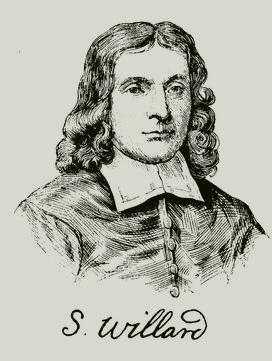

Simon Willard

Founder of Concord MA

Simon Willard (1605–1676) was an early Massachusetts fur trader, colonial militia leader, legislator, and judge.

Simon Willard was born in 1605 in Horsmonden. In May 1634, aged 31 years he went to America and was one of the founders of Concord, Massachusetts and in one of its suburbs a granite boulder inscribed to his memory.

“The Grandee of Massachusetts.”

“The Grandee of Massachusetts.”

“The Kentish Soldier from Horsmonden.”

Born: 1605 in Horsmonden, England

Died: 1676, April 24. Aged 71. Charlestown, Massachusetts

Buried: Charlestown? Groton? Where??

Wives: 1. Mary Sharpe 2. Elizabeth Dunster 3. Mary Dunster

Through his 17 children, 14 of whom propagated, he had a big part in settling new towns to the west, south and north of Concord. His progeny today add up to more than one million people, located the world around.

Back in the birthing stages of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Crown of England declared that in order to start a new town there must be two leaders – a religious leader and a military leader – to be in charge of any group of pioneers who were ready to pool their resources and set forth into a new settlement.

Well, among the arrivals in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the year 1634, was a certain Reverend Peter Bulkeley, who had recently been ousted from his pulpit in Odell, England, through Bishop Laud, because he was not preaching to his parishioners the things that King Charles I wanted them to hear. Bulkeley’s beliefs and preaching were not acceptable, so he came to the Colonies seeking another band of Puritans who would like to follow him.

And, at the same time, came a certain Simon Willard, age 31, with a young family, who had a background of military training in the British Army, held the rank of Major, and who was also an adventurous merchant bent on setting himself up in the business of fur trading and a great humanitarian as well.

So here were the two required leaders and a group of twelve or so families ready to expand into the wilderness, seeking a new and good living.

The earlier European explorers, who had landed on this coast since the days of Christopher Columbus, had introduced a new trade to the gentle folk of England and the European continent – that of buying furs from the Indians of the New World. Here there were: wolves, bears, elk, moose, deer, mink, otter, martin, raccoon, fox, woodchuck – and best of all – beaver. The fur of the beaver had top priority because it was preferred for its beauty, durability, warmth and weight. The high fashion of the day in London and Paris had become tall beaver hats for gentlemen, beaver capes for ladies, beaver robes for their carriages and sleighs, and even beaver-covered Bibles were to be had. So the traders urged the American natives to produce all the skins they could find, and this was easy since there was such an abundance of them in these forests and waterways.

In exchange, the Indians wanted things from the Englishmen, such as iron kettles, axes, metal tools, guns and powder, ribbons, ornaments, blankets, liquor, etc. So the beaver became the staple of the New England fur trade and of special importance to the economy of the Colonies. From 1631 to 1636 the Massachusetts pilgrims had sent 12,000 pounds of furs to England, which helped them to pay off their debt to the Mother Country promptly for the money borrowed to make their trip to the New World in the first place. The furs sold for 20 shillings per pound.

Simon Willard had probably set himself up in the fur-trading business back in Horsmonden. Since he had been apprenticed to a merchant, he was learning to be a good businessman, and that probably was the prime factor in his decision to undertake this adventure in 1634.

At any rate, once he arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and had his family settled comfortably, his adventurous spirit lured him into the wilderness, seeking the source of his furs. He ventured out beyond the protection of the Bayside villages following obscure Indian paths, and found himself in Musketaquid land, the Indian word for this Concord area – “Grassy rivers.”

Musketaquid was the heart of the beaver territory because of the numerous waterways that form the Sudbury and Assabet rivers, which meet at a place in Concord called Egg Rock, and from that point on it becomes the Concord River. It was near to the Indians of the Merrimack Valley and the Nashaway natives. For 10,000 years aboriginal people had been living here, and the Algonquian tribe had had a high civilization thriving in this area.

But those European explorers who had come ashore here to mingle with the natives had also brought their dreaded diseases of smallpox, measles, diphtheria, etc. There would be periods of the epidemics spreading through the Indian camps and the natives, having no natural immunities in their bodies for foreign germs, would die in great numbers. Thirty or forty a day would expire and their bodies were burned to hopefully put an end to the epidemic. There had been a bad disaster in 1617 and another in 1633, so when Simon Willard came upon this land, and found the place practically empty, but with fertile land ready for seeding, and this “pre”pared location already cleared of trees and rocks, it seemed like an ideal place to start a new community. Also from this Musketaquid region, Simon could better intercept the furs coming from the Nashaway and Merrimack and Pawtucket tribes, and no doubt this cut off trade for the Truck House in Cambridge, which was the outermost Trading Post for the Mass. Bay Colony at that time (corner of Mt. Auburn and Brattle Streets in Cambridge today).

How did Simon know this little secret? Apparently through a friend from Kent, England – William Wood – an enterprising man, who had sailed to these shores with a crew of adventurers bent on investigating this wilderness to find out about its resources. He kept an accurate log, to which he added his own remarks, and when he returned to Kent, wrote a book about it, which was published in London in 1634, titled New England Prospects.

I am fortunate enough to have inherited a copy, since my husband and I are both descended from this man, William Wood.

So, Simon made friends with the Indians and learned to speak their language so that he could do business with them. He was a very honest man, never cheated them, and they trusted him; so there was never any trouble nor harassment from them in our town, and that led to the naming of our town because the settlers lived in peace and harmony and “Con-Cord” with the native people.

Concord became the first “inland” town in America to be established away from the Atlantic Ocean – therefore a real pioneer town, “a seed town” from which the 2nd and 3rd generations spread out to start more new towns to the west, north and south. It became a “shire town,” where the Court House held all trials of wrongdoers at the sessions held twice a year, spring and fall, and being on the stagecoach route, inns and taverns became prevalent.

Since Simon had dealt so fairly with the Indians, he was instrumental in the actual transaction of buying the land from them. This Englishmen’s concept of “buying” the land puzzled the Indians greatly because they did not “buy” things – they swapped things, value for value, or gave things away – a policy of give and take, and a fair exchange for something they wanted. And they didn’t own the land – “it belongs to the Great Spirit – and we use it and take care of it, but it’s not ours to give.” As the great Chief Seattle asked: “How can I sell you a cloud?”

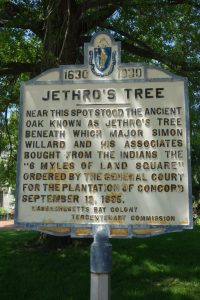

But the Englishmen insisted they needed to know where their bounds were. So the groups met under the Great Oak Tree – Jethro’s Tree – in the center of town, as it is now – five or more Englishmen and Squaw Sachem with several of her braves and they made a bargain agreeable to all. She asked for hatchets, hoes, knives, a little Wampumpeag (their form of money), but mostly the braves wanted cotton shirts, and Webbacowet wanted to look like Simon Willard, so they gave him a white shirt, a white linen band, a tall hat, shoes, white stockings and a great coat. Then Simon Willard set the bounds of the town by pointing to the four directions: 3 miles north, 3 miles east, 3 miles south and 3 miles west, making a six myle square area the white men could call theirs, and Squaw Sachem was satisfied. The natives could keep their hunting rights which were very important to them. This measurement of land became an example for other towns to follow.

Simon was a man of means, and held in high esteem as a merchant. He owned a 1,000 acre tract of land in Concord and Acton, which he sold as he was leaving Concord to go to help the town of Lancaster that was being besieged by unfriendly Indians. The Concord land was bought by the proprietors of the Saugus Iron Works who set up a new Iron Works in Concord by the Assabet River after they found a good supply of bog iron there.

About Simon’s personality – Clara Endicott Sears (whose estate in Harvard, Massachusetts, is now a museum called “Fruitlands”) describes him as “a dashing personality, strong, tall, of good birth, great wisdom, handsome.” Here is a quote from Concord Town Records: “He was held in high regard by his townsmen for his character, ability and shrewd but honest dealings with white men and Indians alike.

They leaned heavily on him for Council, and, when 23 years later, the Town of Lancaster sent an invitation to “Come and inhabit among us” – it was with heavy hearts that they let him go.”

This could have been a smart move on Simon’s part, as perhaps another lure was to be able to take over the Truck House there, and intercept the Connecticut River Valley fur trade. Here there would be fewer Englishmen and fewer rivals.

In case you are not convinced that Simon was a busy, capable, intelligent, efficient and wise man, try reading the five columns of his achievements during his lifetime in the index of the massive book Willard Memoir; or Life and Times of Major Simon Willard, 1858 edition, by Joseph Willard. In the copy reproduced by Higginson Books of Salem, Massachusetts, there are 146 items mentioned of things he did. Ruth Wheeler suggests that perhaps Simon Willard was the one to name Walden Pond in Concord, after a place in England called Saffron Walden, and in honor of a Major Walden, who was also a fur trader and a contemporary of Willard.

A description of his death and funeral are available in Life and Times of Major Simon Willard. There had been a bad epidemic of a lung disease (influenza?? pneumonia??) in April 1676 in Charlestown, Massachusetts. Simon’s house in Groton (town of Ayer now) had just been burned to the ground by savage Indians, and he had moved his family to a safer place in Charlestown. Shortly after his move he was stricken with the plague, and died within days of being ill, “struck down by a fatal disease, died from a plague of an epidemic cold.” Six hundred people died at that time.

“Several hundred soldiers marched, companies of foot and companies of horse marched to Major Willard’s funeral, then marched to Concord. There were probably crowds of public people to honor him.”

But his gravesite is still unknown. It is not recorded in Charlestown. To quote from Wyman: Charlestown Genealogies and Estates, 1879, “died April 24, 1676, here, buried from Groton 27th” – but no one has ever found it that we know of.

Major Simon Willard and his men

Of all the names that stand upon the pages of New England history, none are more honoured than that of Major Simon Willard. His biography has been written in the “Willard Memoir,” and therefore only a brief outline will be necessary here. He was born at Horsmonden, County of Kent, England, baptised April 7, 1605. He was the son of Richard and his second wife Margery.

Simon married in England Mary Sharpe, of Horsmonden, who bore him before leaving England (probably) three children, and six in New England. He married for a second wife Elizabeth Dunster, who died six months after her marriage; and a third wife, Mary Dunster, who bore him eight children, between the years 1649 and 1669.

Simon Willard arrived in Boston in May, 1634, and settled soon after at Cambridge. He was an enterprising merchant, and dealt extensively in furs with the various Indian tribes, and was the “chiefe instrument in settling the towne” of Concord, whither he removed at its first settlement in 1635-6, and remained for many years a principal inhabitant of that town.

On the organisation of the town he was chosen to the office of clerk, which he held by annual election for nineteen years. It is said upon respectable authority that he had held the rank of captain before leaving England, and in Johnson’s “Wonder Working Providences” he is referred to as “Captain Simon Willard being a Kentish Soldier.” In 1637 he was commissioned as the Lieutenant-Commandant of the first military company in Concord.

At the first election, December, 1636, he was chosen the town’s representative to the General Court, and was re‰lected and served constantly in that office till 1654, except three years. In that year he was re‰lected, but was called to other more pressing duties; and afterwards to his death was Assistant of the Colony.

In 1641 he was appointed superintendent of the company formed in the colony for promoting trade in furs with the Indians, and held thereafter many other positions of trust, either by the election of freemen or the appointment of the Court, too many to admit of separate mention here. In 1646 he was chosen Captain of the military company which, as Sergeant and Lieutenant, he had commanded from its organization.

For many years he was a celebrated surveyor, and in 1652 was appointed on the commission sent to establish the northern bound of Massachusetts, at the head of Merrimac River, and the letters S W upon the famous Bound-Rock (discovered many years ago near Lake Winnepesaukee) were doubtless his initials, cut at that time. In 1653 he was chosen Serjeant-Major, the highest military officer of Middlesex County.

In October, 1654, Major Willard was appointed commander-in-chief of the military expedition against Ninigret, Sachem of the Nyanticks, as told heretofore, in the Introductory Chapter, p. 22. In the settlement of the town of Lancaster Major Willard had been of great service to the inhabitants, and their appreciation was shown when, in 1658, the selectmen wrote him an earnest invitation to come and settle among them, offering a generous share in their lands as inducement. This invitation he accepted, sold his large estate in Concord, and removed to Lancaster, probably in 1659, and thence to a large farm he had acquired in Groton, about 1671, at a place called Nonacoicus.

At the opening of “Philip’s War,” Major Willard, as chief military officer of Middlesex County, was in a station of great responsibility, and was very active in the organization of the colonial forces. His first actual participation in that war was in the defence of Brookfield, the particulars of which have been noted. We must admire this grand old man of seventy, mounting to the saddle at the call of the Court, and riding forth at the head of a frontier force for the protection of their towns. On August 4th he marched out from Lancaster with Capt. Parker and his company of forty-six men, “to look after some Indians to the westward of Lancaster and Groton,” having five friendly Indians along as scouts, and, receiving the message of the distressed garrison at Brookfield, promptly hastened thither to their relief, which he accomplished, as we have seen in a former chapter. Upon the alarm of the disaster at Brookfield, a considerable force soon gathered there from various quarters.

Two companies were sent up by the Council at Boston, under Captains Thomas Lathrop of Beverly and Richard Beers of Watertown, and arrived at Brookfield on the 7th. Capt. Mosely, also, who was at Mendon with sixty dragoons, marched with that force, and most of Capt. Henchman’s company, and arrived at Brookfield probably about August. From Springfield came a Connecticut company of forty dragoons under Capt. Thomas Watts, of Hartford, with twenty-seven dragoons and ten Springfield Indians under Lieut. Thomas Cooper, of Springfield.

These forces for several weeks scouted the surrounding country under Major Willard; the details of which service belong properly to the accounts of the several Captains. In addition to these were forty “River Indians” from the vicinity of Hartford, and thirty of Uncas’s Indians under his son Joshua, who scouted with the other forces. The Nipmucks could not be found, and it was afterward learned from the Indian guide, George Memecho, captured by the Nipmucks in Wheeler’s fight, that on their retreat from Brookfield on August 5th, Philip, with about forty warriors and many more women and children, had met them in a swamp six miles beyond the battle ground, and by presents to their Sachems and otherwise had engaged them further in his interest; and all, probably, hastened away towards Northfield and joined the Pocomptucks, and thence began to threaten the plantations on the Connecticut River.

After several days diligent searching, on August 16th, Captain Lathrop’s and Beers’s companies, the latter reinforced by twenty-six men from Capt. Mosely, together with most of the Connecticut, Springfield and Indian forces, marched towards Hadley and the neighboring towns, while Mosely went towards Lancaster and Chelmsford. Major Willard remained for several weeks at the garrison. Mr. Hubbard and Capt. Wheeler make this statement, and further relate that he soon after went up to Hadley on the service of the country.

I think the visit to Hadley was after August 24th, as on that date I find a letter from Secretary Rawson to him, enclosing one to Major Pynchon, and advising him to ride up to Springfield and visit Major Pynchon “for the encouragement of him and his people.” The writer of the “Willard Memoir” states that he was in command of the forces about Hadley for some time in the absence of Major Pynchon, but I have been unable to find any confirmation of this, unless it may be the inference drawn from Hubbard, who states that when Major Willard “returned back to his own place to order the affairs of his own regiment, much needing his Presence,” he left “the Forces about Hadley under the Command of the Major of that Regiment.”

The letter above contained directions about the disposal of his forces, etc., which would naturally take several weeks to accomplish, and although the precise date of Major Willard’s return from Brookfield is not given, some inference may be drawn from circumstances noted further on.